Grell OAE-1: Why You Shouldn't Care About Soundstage

Grell's new OAE-1 has some rather unique design goals: extreme openness and frontal driver orientation. Join listener as they evaluate the headphone, the theoretical underpinnings of its design and marketing, and why consumers should be a lot more skeptical when a headphone is claimed to have "speaker-like soundstage".

The Grell OAE-1 has been a long time coming. While this review is going to be negative, that doesn’t mean I haven’t been anxiously anticipating this headphone’s release.

To my mind, there isn’t a single headphone designer with more name recognition and a better track record than Axel Grell. His history leading up to now is one marked with high highs and low lows, but I don’t think anyone can deny his influence being among the most important forces to ever propel the creation of audiophile headphones.

As someone who respects him immensely as a designer, I think it’s important for me to disclose the degree to which I am biased in Axel Grell’s favor. He is responsible for some of the greatest headphones of all time, and more importantly, he’s been an absolutely lovely man whenever I’ve had the good fortune to talk with him at audio shows.

That said, it’s also important to disclose that some of the ideas underpinning the OAE-1’s design are… unique. With the OAE-1, Axel Grell has sought to implement ideas previously explored in prior designs like the HD 800, the main two being:

- Extremely low acoustic impedance of the front volume. In layman's terms, an extremely open design

- “Speaker-like” imaging and soundstage due to forward incidence of the driver

After considerable testing, I have to say that I’m a bit skeptical about these ideas being achieved, or even worth targeting to begin with. I’m even more unsure about this headphone’s viability in an increasingly competitive market.

This is going to be quite a bit longer than my usual product reviews, because here I must give my take on the headphone’s sound, but also discuss the ideas that underpinned its creation and marketing, as well as why consumers should be a lot more skeptical when headphones like this claim to have speaker-like soundstage.

I’d go as far as saying this headphone is one of the best examples I’ve come across regarding why headphone consumers shouldn’t care nearly as much about “soundstage” as they currently do. But we’ll get into that a bit later. For now, let’s talk about the Grell OAE-1.

What we like

- Probably one of the best looking over-ear headphones I’ve ever seen

- A risky release in a time when very few companies are taking risks

- Not incredibly expensive if one wants to try something non-standard

What we don’t like

- Comfort is unilaterally poor

- Frequency response tuning will almost certainly be perceived as colored

- Drastically underperforms in all subjective sonic qualities

Part One: Grell OAE-1

Build, Design, and Comfort

I love the look of the OAE-1, and it might be the best looking headphone released this year. It’s a minimal enough design such that no part seems extraneous, the silhouette is sleek and modern, and the colorway is flatteringly simple. Honestly, I think this might be one of the better looking headphones of all time… but unfortunately the mechanical design in practice isn’t quite as praiseworthy.

One improvement that was made since the demo I had at CanJam NYC 2024 is that they lengthened the headband extension arms so when fully retracted, they no longer fully “disappear” into the headband. This was a necessary move, as people at multiple CanJams couldn’t fit the headphone on their head due to the arms not being long enough. Unfortunately, they kept the same uncomfortably small headband pad, which leads us to our first negative.

I get a pretty punishing hotspot on the top of my head within 10 minutes of wearing this headphone, at which point I either have to reposition it, or take it off entirely. Drop has said they’re working on a different headband pad, so owners should keep an eye out for that in case they have the same problem, but in its current state I have to say its among one of the least comfortable headbands I’ve used.

The earpads are a fairly stiff memory foam wrapped in soft velour, similar to the material used for the HD 6 series pads. The ear cups are circular (instead of ear-shaped) as well as too small for me, so my earlobes get a bit smushed, causing immediate discomfort. Adding this to the above headband padding issue and to the considerable clamp force means OAE-1 really falls short in the comfort department for me. Surprisingly so, given the design this headphone first reminded me of—Sennheiser’s HD 800—has some of the best comfort of any headphone I’ve used.

One thing readers should note is that the cable connectors of the headphone are a little unique. The jacks on the ear cups have little “sleeves” that the cable connectors plug into that seem to help with the jacks themselves not contributing any air leak to the system.

This is a good idea for inexpensive closed back designs, but I don’t actually think it was necessary here—especially because this sleeve protruding from the ear cup seems to have confused users. Many owners in the Head-Fi thread found that they were listening with one or both cables partially-disconnected, so make sure when you try this headphone that both connectors are securely connected to the terminals (you should hear a click).

In terms of build, I don’t have any reasons to be worried about the longevity here. Most of the build seems to be plastic, and it’s not an especially heavy headphone, weighing just under 400g. If anything the main issue I’m worried about is the tension on the arm extensions—which lack any click as they retract or extend—loosening over time.

Overall, the build is solid, the visual design is fantastic, but the mechanical design and comfort need considerable work. Unfortunately not off to a great start, because comfort is super important to me.

Frequency Response and Tonality

Above is an averaged L+R measurement of the Grell OAE-1, measured on two different rigs. First in blue is my rig, consisting of a clone 711 coupler + clone KB006x, and the second in magenta is my friend’s clone 711 + clone KB50xx pinnae rig. This is to show the degree of variation between two different heads, and thus both are calibrated to each head’s respective Diffuse Field HRTF—which is necessary for this type of comparison. Below is the same measurement as the blue trace above, displayed raw/uncalibrated (and solely on my rig).

Bass

The bass of the OAE-1 swamps the midrange near-entirely, but this being a good or bad thing depends on your perspective. Personally, this is the exact kind of bass that I try to avoid, both in personal use and in recommendations to others. It is overly bloomy and causes a noted imbalance towards a kludgy and slow presentation. For anyone who wants something balanced, OAE-1’s bass takes it out of that conversation immediately.

There’s an indistinctness to pianos that’s rather hard to ignore, considerably blurring their sonic image. Acoustic guitars sound a bit suffocated due to the overemphasis of everything under 500 Hz, while bass guitars sound biased toward their early harmonics and sound a bit swollen as a result. Kick drums sound suspiciously similar to how they sounded on the gaming headsets I used as a teen: over-warmed, and—spoiler for the treble section—clacky.

On the bright side, there are at least two potentially good things about the bass of this headphone that are worth touching on, even though they don’t really improve my experience:

- The headphone itself has very solid bass extension, which I assume is due to the stiff component of its biocellulose diaphragm making for a very low free-air resonance frequency.

- The headphone’s bass extension is rather resistant to leaks, which means it will likely have very consistent bass performance across different head shapes or hair lengths.

Neither of these attributes make the headphone sound very good on their own, but if you’re the type of person who likes EQ, these are rather uncontroversial upsides for that approach. But otherwise, I’d not say the bass presentation here is particularly special or worth chasing.

Midrange

The midrange in isolation could actually be a lot worse here, but it’s still got some important downsides to touch on. Before we even talk about the midrange proper though, it must be reiterated that the bass near-completely overshadows most of the midrange, such that almost everything is lacking in intelligibility. This tuning choice means that my first instinct with OAE-1 is to raise the volume more than I do with other headphones—but for reasons we’ll get into in the next section, I really don’t enjoy it at higher volumes.

On its own, the midrange is fairly similar to a lot of the headphones coming out these days like the Meze 109 Pro, Sony MDR-MV1, or most of the Hifiman egg-shaped headphones. There’s a notable 1-2 kHz scoop followed by a late (and rather intense) 3 kHz ear-gain rise, and the former definitely contributes to the indistinctness mentioned prior, especially on vocals, pianos, or stringed instruments.

It’s a little nitpicky, but this is the most important part of the audio band. Am I the only one incredibly tired of headphone manufacturers not bothering to get this part really right? Rant for another time, I suppose.

I tend not to like this midrange presentation in open-back headphones, but plenty of other people do. So while I’ll be firm in saying that the way it clouds up most things isn’t very good for me, those who tend to prefer a significantly warmer midrange might end up liking this tuning choice. While the midrange is warm here, I wouldn’t call OAE-1 free of harshness. I think the midrange to treble transition point is likely to cause issues for people who want a warm, cozy midrange, but we’ll touch on that in the next section.

For now I’ll say that from a zoomed out perspective the overall “shape” here would be fine in isolation. But it’s not very well integrated with what’s happening above and below it in frequency.

The bigger issue lies in an area that is either the end of the midrange, or the beginning of the treble depending on who you are. So I’m going to take this opportunity to dive right into the treble… because that’s where this headphone gets—for lack of a better term—weird.

Treble

The treble of this headphone is upsetting enough that it compelled me to shoehorn in an entire separate article’s worth of educational content in the back half of this piece just to talk about how this treble tuning doesn’t make sense for any headphone.

But we’ll get to that later. First, let's just talk about how it sounds.

There is a sizable 4-5 kHz peak that gives this headphone a particularly fatiguing, scratchy, dry character that’s quite reminiscent of the Sennheiser HD 5 series open backs… but much worse.

The elevation here makes snare drums sound like they are made out of pure concrete, while the drum sticks are replaced with metal hammers wrapped in sandpaper. There’s a fatiguing, teeth-gnashing “hardness” to the front end of most transients that somehow makes an exceedingly warm and bassy headphone also shockingly harsh.

It’s made even worse by the fact that immediately after this peak, you get a 6-7 kHz dip on the order of a 10-20dB difference from the 4-5 kHz area before it. This is not just an innocuous narrow-band resonance that will vary between heads or placements. If measurements on different rigs are anything to go by, this peak-into-dip will likely be present on many heads in some shape or form because of the frontal incidence of the driver.

We will be coming back to this, and why it wasn’t actually a good idea, but if all you care about is the sound: it’s a cavernous medium-Q dip in a region we’re incredibly sensitive to. It’s likely you will hear it, and it’s also likely that you will hear it as a coloration.

Moving to the upper treble, there’s a rockiness making most cymbals sound hashy and gritty. It’s not unlike the experience I’ve had with the upper treble of the Fostex TH900 or EMU Teak. It compounds with the rollercoaster of a treble tuning preceding it to make the treble sound wholly erratic and absent any sense of cohesion. Somehow it is the least offending part of the treble here, which is rare for my reviews, but it is still not well-handled on its own.

It might be clear after going through the frequency response, but in case it isn’t: none of this treble tuning makes any sense to me. Why on earth did Axel Grell, the man responsible for the greatest headphones of all time (do not @ me) tune his newest headphone this way?

What Happened Here, and Why Are People Buying This?

As previously stated, the OAE-1 implements two ideas from prior designs from Grell like the HD 800:

- Goal #1: Extremely low acoustic impedance of the front volume (in layman's terms, an extremely “open” design)

- Goal #2: “Speaker-like” imaging and soundstage due to forward incidence of the driver

I’ve gathered from his CanJam presentations that #1 was the primary goal for this design, but I don’t quite have the equipment to properly test how low the acoustic impedance actually is. I’d say it subjectively has a fair amount of openness, at least on par with the HD 660S2 I have on hand, but not quite as open feeling as my HD 800.

#2 is the one I really have problems with though, because while it is partly responsible for making this headphone interesting in a marketing sense… it is also largely responsible for this headphone not being good.

Grell’s Hypothesis

Axel Grell seems to believe that the ideal tuning for a headphone with such an open environment and a frontal driver placement would be the same as well-tuned speakers directly in front of the listener in a normal free-air listening environment.

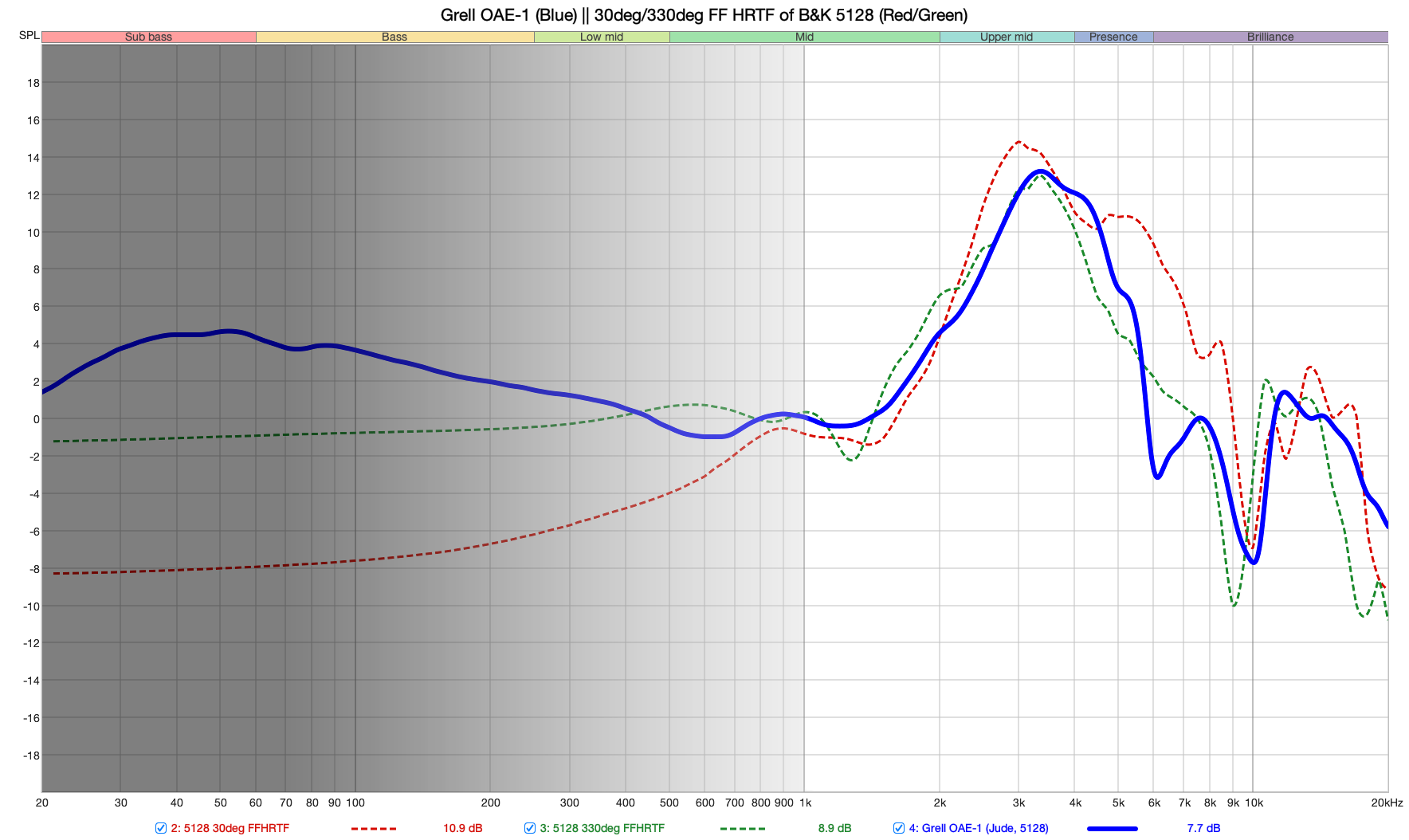

The red and green traces above are flat EQed speakers at a ±30 degree angle measured in an anechoic chamber in front of the B&K 5128, and the blue trace is OAE-1 measured on the same rig. Note the similarity above 1 kHz, below which I’ve grayed out to illustrate the former’s importance.

Placing the driver of the OAE-1 at such a dramatic frontal incidence does actually make it measure closer to an anechoically flat speaker placed in front of the listener. After reading my evaluation above, readers know this didn’t make OAE-1 sound “good” to me. So doing this resulted in a tuning that sounds fundamentally weird to me, but does this engender the desired psychoacoustic effect of making the listener hear the sound as coming from the front?

It doesn’t. And the reason why is… well, it’s complicated.

The short and minimally-nerdy answer—and all that is really needed to recommend against purchasing OAE-1—is that there is a strong psychoacoustic case for this type of tuning not being appropriate for headphones, and various research bodies have fairly robustly debunked this kind of tuning being a good idea.

The long answer involves debunking the marketing directly, and stating (with evidence) why a passive headphone design—even one like this—cannot have proper externalization or “speaker-like soundstage” without advanced DSP.

Unfortunately, no one else has challenged the very specific marketing about this headphone being optimized for this “speaker-like” effect, and many audiophile consumers are falling for the marketing.

There are two fairly consistent reactions I’m seeing among OAE-1 owners using as an excuse for its poor frequency response:

“This headphone was tuned to measure like a speaker in front of the listener. So even if the tuning is bad, the soundstage has to be incredible, right?”

—or—

“This headphone is not supposed to be judged against other good headphones, because it’s so unique it should be judged by some other rubric.”

This is a pretty glaring example of audiophile consumers being incredibly prone to uncritically believing the claims of marketing when they don’t have the information necessary to rebuke it.

Thus, the long answer is needed.

No one else is telling consumers how actually nuanced the idea of “headphone soundstage” actually is, so it falls upon me to explain exactly why this line of thinking is so flawed, and why you shouldn't buy Grell OAE-1—or any headphone—tuned explicitly to the sound of a speaker directly in front of the listener.

Part Two: Soundstage Is More Complex Than You Think

While readers may be used to the concept of soundstage as a key factor in 'good' headphones, I’d like to ask that readers keep an open mind about the contents of the following section. There is much to be discussed regarding soundstage that isn’t often discussed elsewhere, such that if readers approach this with an open mind they may well find themselves being exposed to brand new information, and a new model of understanding soundstage. “Soundstage” is a term that’s been bandied about for decades related to headphone sound quality. It’s incredibly ubiquitous, enough so that it’s perhaps the only term from the audiophile lexicon to have a consistent foothold in the minds of non-audiophiles. I never see tech youtubers, studio engineers, or gamers talking about dynamics or timbre, but I seem to see all of them talk about soundstage pretty commonly.

They’re often talking about different things, or don’t even know what exactly they’re talking about because they’ve never heard it before.

Even if the term clearly means different things to different people, I think the core idea of a headphone’s bounds of space being more “externalized” than usual is a common thread to most people’s definitions. However, I’ve seen many such people think it can make a headphone sound like speakers, or that a headphone with good soundstage could even make music sound like it’s being played by musicians in the room with you.

The problem is that’s… not really how headphones work.

If one seeks literature to learn more about how externalization, spaciousness, or anything resembling “soundstage” could possibly be quantified, all roads lead to one conclusion: There may not even be such a thing as soundstage in headphones.

What Is (and Isn’t) Soundstage?

Before I go deeper, I want to make sure that people know that a lot of this has been covered in my article about Diffuse Field, which you should read if you want to know more about why we at Headphones.com use Diffuse Field, and why tunings like OAE-1 have long since been abandoned by most people making audiophile headphones.

Humans have an incredibly complex and precise hearing system, and how we orient ourselves within the space of our three-dimensional world is owed in large part to how this system works. I love when this system is engaged in media with audio delivery systems like “binaural” audio—which is generally recorded with a dummy head to replicate the directional and tonal effect a human’s head and body would have on incoming sound—and “surround sound,” which delivers immersive and at times even hyper-realistic content by placing multiple sound sources around the listener.

These are likely the best examples of “soundstage” we have in the world of audio content. Either can be extremely convincing when done right, so it’s worth unpacking how and why it works, because with that knowledge comes understanding regarding how the human hearing system itself works, and what factors need to be considered for an ideal experience of “soundstage” for headphones.

So first, let’s talk about three critical factors that underpin human localization—a.k.a. the ability to locate sound sources in space solely based on their sound.

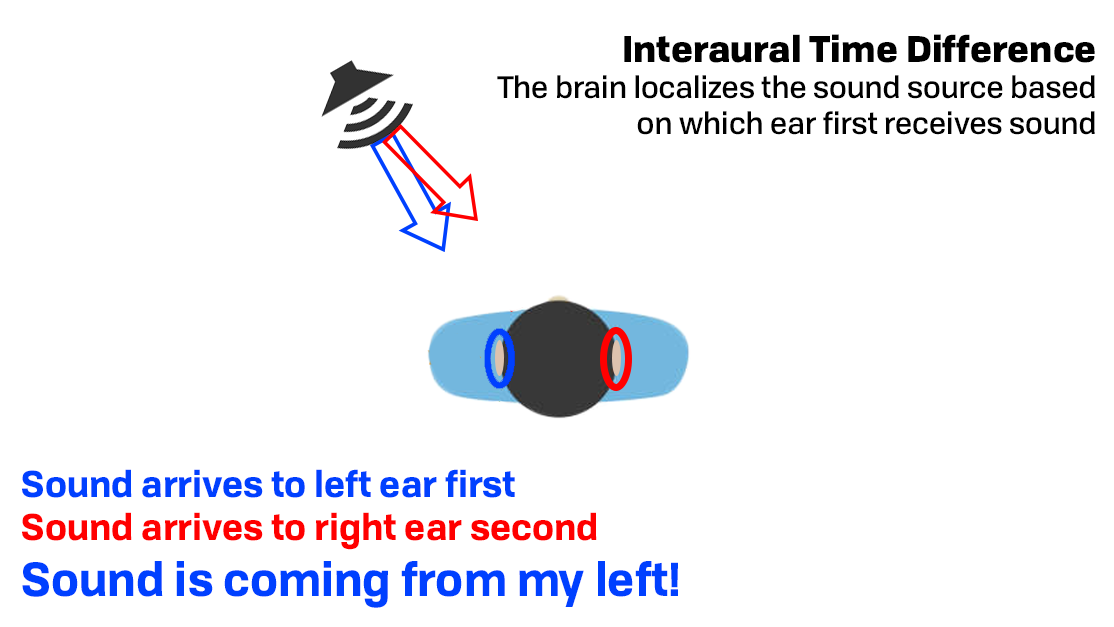

Interaural Time Difference (ITD)

Most of us have two ears, and our brain is constantly unpacking the signal differences between them to determine where sound sources are located. Part of this includes unpacking Interaural Time Difference (ITD), or the difference in a sound’s arrival time between your two ears.

As shown in the example above, if a sound arrives at one ear before the other, our perception of the sound will be biased to whichever side received the sound first.

We humans are quite good at discerning the difference in timing between our two ears, but we don’t notice this time difference as a time difference. ITD is part of the larger localization process handled by the brain unconsciously, so instead of thinking “the sound is arriving 15 milliseconds earlier to my left ear than my right ear,” we only think “the sound is coming from my left.”

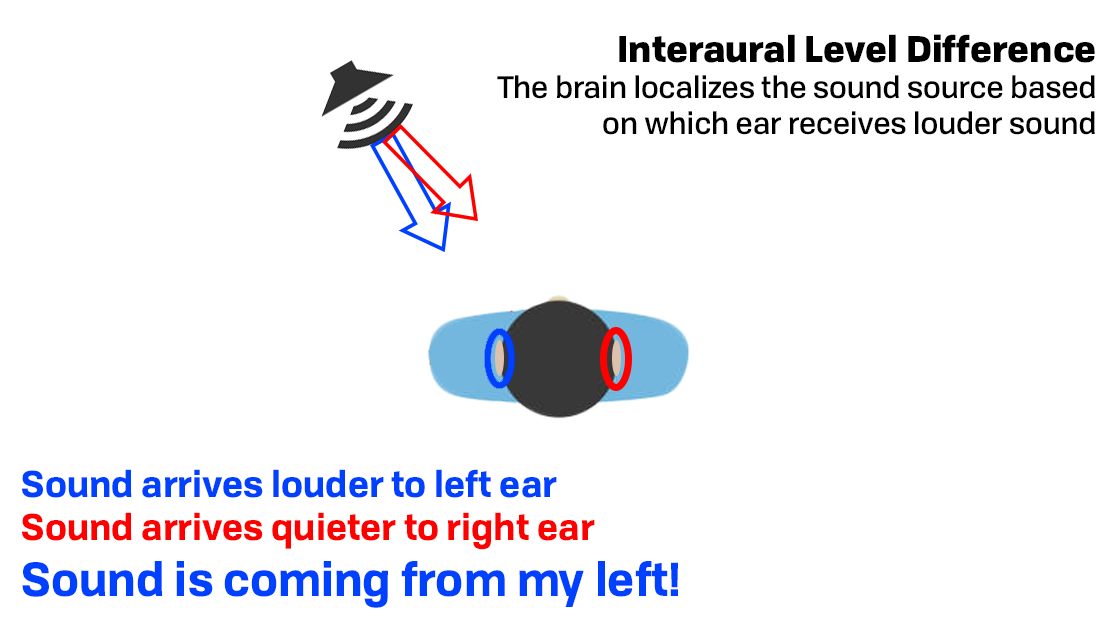

Interaural Level Difference (ILD)

ILD is even simpler: The ear closest to the sound source will receive a louder sound than the ear that is farther from the sound source. And again, the brain unpacks this unconsciously as part of the larger localization process.

Which means we don’t really hear “this sound is 3dB louder in my left ear than my right ear,” but instead “the sound is coming from my left.”

Head-Related Transfer Function (HRTF)

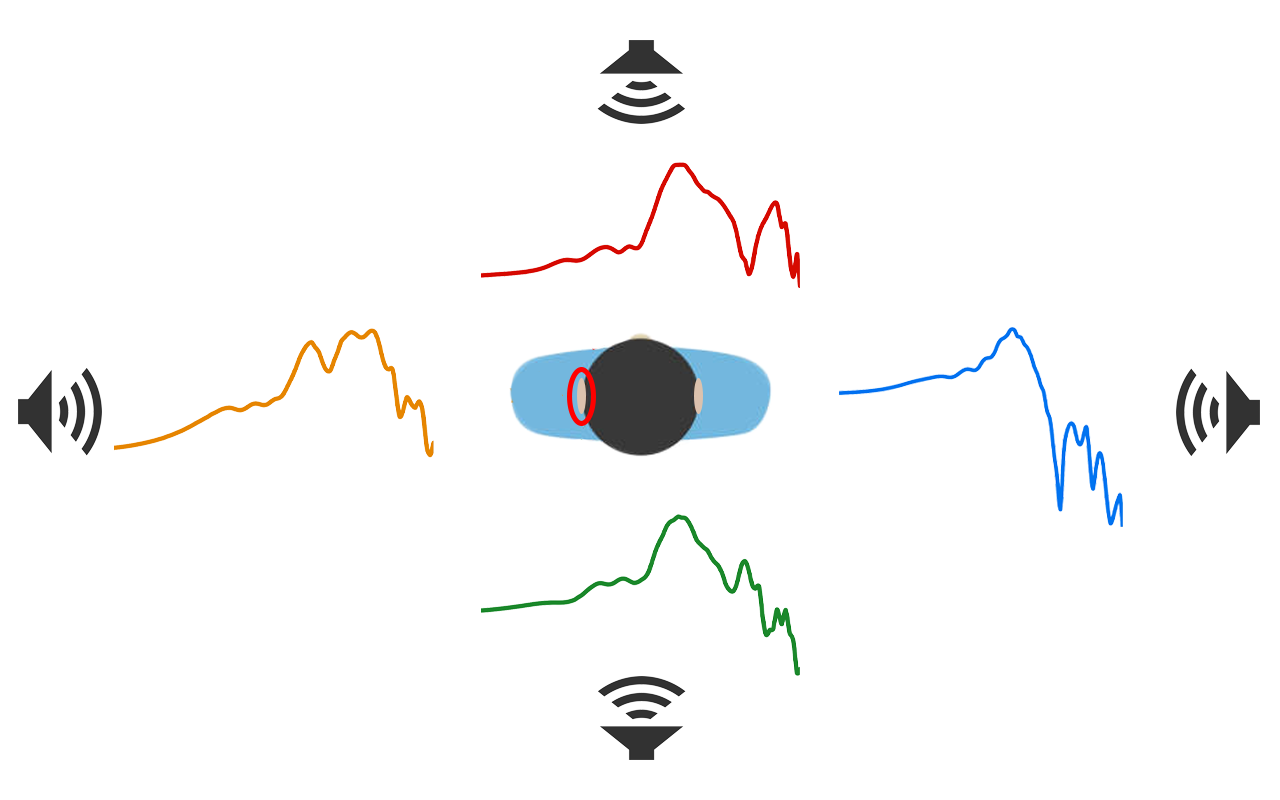

Sounds emitted from physical sound sources in the real world are transformed in frequency response by your body, neck, head, and ears before they reach your eardrum. How they’re transformed depends on your anatomical features, as well as the relative angle (azimuth) and elevation of the sound source relative to your ear.

Say we’re in an anechoic chamber, and we have a speaker that measures flat with a traditional omnidirectional measurement microphone.

0º, 90º, 180º and 270º Free Field HRTFs of the B&K 5128, measured at a single ear (circled)

When this anechoically-flat speaker is measured at different angles of incidence relative to the left ear of a listener—or in this case, a B&K Type 5128 Head and Torso Simulator—we would see measurements taken at the left eardrum look like the above curves. The speaker placed directly in front of the head would look like the red curve, and the same speaker when placed on the opposite side of the head to the ear would look like the blue curve, etc.

These frequency response transformations—called Head-Related Transfer Functions (HRTFs)—exist for every angle and elevation around you, and these transformations are always affecting incoming sounds for both of your ears in the real world.

So when we hear something to the left, we’re not only hearing the sound arriving first at our left ear (ITD), or arriving louder at our left ear (ILD), but also hearing specific frequency response cues in both ears that our brain has correlated to leftward positioning.

If that all sounds incredibly complicated, that’s because it is.

However, our brains are insanely clever. As with ITD and ILD, we don’t consciously hear “wow, the sound at my left ear has a lot more upper mids and treble than my right ear.” We hear “the sound is coming from my left.”

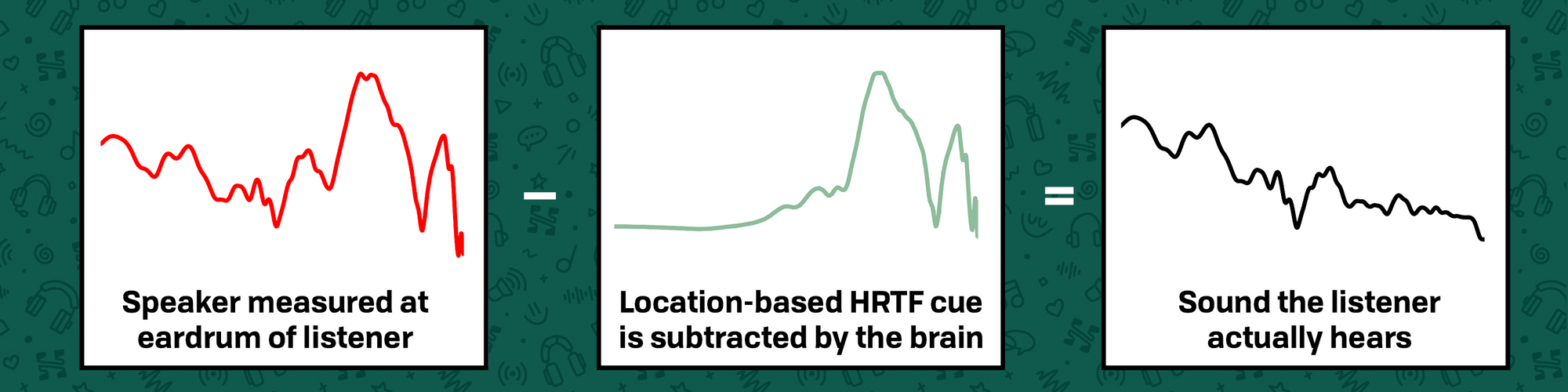

I cannot overstate the importance of the implications here. This means that we don’t hear massive swings in frequency response arising from sound source incidence, because our brain is constantly subtracting these frequency response cues from our perception.

With speakers, we hear past any of the chaotic-looking HRTF-based frequency response cues only hearing “the tone of the speaker itself,” and it’s the same in all normal real-world listening!

Even though the frequency response at our eardrums is probably bonkers after going through the different location-based transformations of our HRTF, our brain removes the localization component of the perceived sound to leave us with “the sound”.

Why This Matters

The reason I bring all of this up is because once you move to headphones, none of this happens.

- Headphones don’t have any ITD, as both channels play simultaneously.

- Headphones (ideally) don’t have any ILD. When they do, it’s channel imbalance, and we hear it as channel imbalance. We would not hear a 3dB imbalance favoring the left channel as “localized as a sound source in the room located to my left,” but instead as a difference in panning within the bounds of normal stereo headphone listening.

- Headphones do not have a full HRTF interaction, because they do not interact with your full anatomy at a specific angle or elevation. They are completely stationary regardless of where your head or body is turned, and they only interact with your eardrum, ear canal, and pinna.

I’ve deliberately boiled it down to as few variables as possible here, but it’s important to note that things like reflections and crossfeed also play a big part in how we understand sound localization in the real world… but headphones don’t have these factors in play either.

If headphones don’t have any of the factors that form the primary makeup of localization, then they can’t really have proper soundstage.

And if they can’t have proper soundstage, what do they have?

Diffuse Localization

A headphone’s frequency response at the eardrum won’t change dynamically based on its location relative to your head, neck or torso, because it’s neither interacting with them nor changing their relative location; headphones are affixed to your head with a constant distance, angle, and elevation relative to your ear.

Because of that invariance of positioning, headphones are devices of “diffuse localization.” And to understand what that means, one needs to understand what a Diffuse Field is.

A Diffuse Field is a circumstance wherein sound is equally distributed at all points of the room and arrives equally from all directions. This means that, unlike the above example where the sound source’s angle of incidence causes a difference in frequency response, the frequency response at any one position in the room would be the same as any other position.

Imagine you’re in a Diffuse Field, and there are a few flat EQed speakers scattered about playing white noise (which would read as flat with a traditional measurement microphone).

Regardless of where you are in the room, the sound would be identical. If you turned your head or your body, the sound would still be identical.

Due to the absence of any frequency response cues to localize the sound sources, the sound would seemingly be emanating from either everywhere, nowhere, or from inside your own head. This “diffuse localization” would be rather unlike any situation you’ve ever experienced in real life, but this is exactly what happens with headphones.

In headphones, no matter how we turn our head, the headphone’s relative angle, elevation, and distance to our ear is constant. This is “diffuse localization,” as it has the exact same timbral invariability as listening in a Diffuse Field would. Regardless of where you’re facing or how your body is oriented, the sound remains the same.

Diffuse localization, in addition to the fact we’re generally not getting ILD or ITD cues, crossfeed, or typical reflections with headphones, means that pretty much all of the important sonic information for how the brain localizes sound is missing. Thus we perceive frequency response—even frequency response that matches a single localization cue—as tonal color, and not as a localization cue.

If the brain had adequate information for localization—the frequency response cues, ITD, ILD, etc. changing as your head moves—it would subtract these cues from our perception and leave us with “the location and tone color of the sound source”. Instead, we are only hearing the frequency response as it exists on our head. And this is why we use Diffuse Field as a baseline HRTF for headphones.

Diffuse Field is absent any of the tonal colorations in frequency response resulting from localization cues, which is necessary because any location-based tonal color will be perceived as solely tonal color, because the brain isn’t removing the localization cue from our perception.

You can tune a headphone to be roughly the same frequency response as a flat speaker at a 30 degree angle in front of the listener, but if you do, the listener is very likely to perceive this frequency response tuning as a tonal coloration, and not as a cue for the location of the sound source.

Part Three: If It’s Not Soundstage, What Is It?

Think about why surround sound works so well when done right: it involves a bunch of real sound sources oriented around the listener, activating the full HRTF around their body, with real ITD, real ILD, real reflections, and real crossfeed such that the localization effect is real.

By contrast, passive headphones like OAE-1 are doing none of these things.

The only real way to get proper externalization or “soundstage” in a headphone is to do exactly what speakers do. ITD, ILD, crossfeed, reflections, and the full HRTF must be simulated for true speaker-like soundstage to occur. It’s a tall order, I admit.

Now, while they don’t really do soundstage, headphones do have a psychoacoustic effect of spaciousness that likely arises from a confluence of frequency response, openness, and ear comfort, and I don’t want to seem like I’m saying this effect doesn’t exist. But this effect is also incredibly subjective, such that you absolutely should not trust anyone’s opinion of it except your own. I also don’t really call this effect “soundstage” anymore, as it’s clearly quite different from actual localization.

For this reason, I consider it important to inform enthusiasts as clearly as possible that they shouldn’t care nearly as much about soundstage as they do now, because it may not even exist. At least not in the way tech youtubers, studio engineers, gamers and product marketing talk about it.

Which brings me back to the OAE-1.

The product page for the OAE-1 makes the below claims about the product:

“A groundbreaking pair of headphones with game-changing driver geometry and an ultra-expansive soundstage. Working in harmony with the body’s innate process for perceiving stereo sound—where we face audio sources so that they’re directly in front of us—the OAE1 Signature positions its drivers further out and in front of the ears to create a soundfield that’s stunningly natural”Now that we’ve concluded Part 2, readers can probably see how this reasoning is fundamentally flawed, and why the OAE-1 is unlikely to deliver the advertised benefits to soundstage or naturalness.

Furthermore, readers now might have a bit more insight into why headphones as a product category are limited in what they can provide in terms of the former without DSP. Thus it probably makes sense to focus on indexing for the things that designers can get right for passive headphones, such as tonality, comfort, build, design (looks), etc.

Part Four: Subjective Evaluations

I’ve covered the reasons why I don’t think “frontal speaker-like soundstage” should’ve overridden good frequency response tuning as a design goal for OAE-1… but that aside, how is the soundstage of the OAE-1?

To me at least, it doesn’t sound frontally-oriented or externalized at all. It just sounds a bit claustrophobic due to excess bass, with an indistinct midrange and a 4-5 kHz peak screaming in my face. There’s a sense of palpable openness, but to be honest it doesn’t make the headphone “disappear” sufficiently on my head because of the headphone’s pads pressing on my earlobes. It’s almost as if the comfort is actually impeding my perception of spaciousness as much as any of the other sonic factors.

The dynamics of the OAE-1 actually weren’t super easy to unpack at first. While the overall warm-tilted tone does steer some moments toward the softer side, the 4-5 kHz elevation is rough enough that transients that would’ve been soft or mushy, instead become annoyingly edgy and chalky. For this reason, I initially found it hard to nail down OAE-1 as being solely “dynamic” or “undynamic”. I had to unpack the term “dynamics'' a bit more, and broaden its definition to “contrast,” where then it became eminently clear to me that OAE-1 is particularly bad at displaying an adequate range of transient contrast.

Everything sounds equally crashy, gritty, and harsh thanks to the lower-treble forwardness, and due to this I’d put Grell OAE-1 squarely in the realm of cheap gaming headsets in terms of dynamic nuance. Even if the 4-5 kHz peak does have the effect of enhancing the transient smack of kick drums in particular, they all get equally and samely enhanced such that the headphone itself just comes across as colored.

In terms of detail… I mean, there’s a giant hole in the treble. And I know that sounds hyperbolic, but a potential 10-20 dB dip of this bandwidth is significant to basically every subjective quality I can think of. I regularly find entire sections of instruments missing such that this is among the lowest “detail” headphones I’m aware of.

That said, it’s not entirely unlikely that the tuning being so weird results in a “new” presentation for some people. It could cause the attention of a listener to be directed to a part of the music that they’d never paid attention to prior. This is potentially one of the most fun parts about hearing new headphones, and it’s what I’d call “detail” more than any single acoustic property. So if listeners are looking for that kind of novelty, OAE-1 might actually provide that… at least at first.

But to me, who’s heard many mediocre headphones and just wants something that sounds “normal in a good way”, I have no real reason to give a pass to something just because it might be “weird in a good way” for someone else. Overall, OAE-1 is just… subjectively unimpressive.

Can It Be Fixed With EQ Or Mods?

This is a topic for an entire other article, but I have reason to believe that headphones with exceptionally-open design schemes like this would be ideal for corrective EQ, because they would vary much less between heads than semi-open or closed headphones.

As such, the best possible future I saw for this headphone was actually as a headphone with a manufacturer-recommended EQ setting, provided with an included QR code in the box or something. The team behind OAE-1 did nothing with this idea, and after testing, I think I know why.

The positional variation for this headphone is significant depending on both the rotation (headband to the front vs. headband to the back) as well as the Z-axis translation (pushed forward towards eyes, or pushed backwards away from eyes) of the headphone on the head.

For this reason, generating a single EQ profile would be difficult, because the sound any one person could be getting on their head could be rather different between seatings, and that’s not even accounting for how different people would wear the headphone differently (or that the deformation of the outer ear caused by the pad shape could make things even more different between seatings/listeners).

Looking at the above, it does seem like rotating the headband forward potentially improves the 4-5 kHz region, and on my head this is the case too. Maybe if the designer(s) of the headphone placed the driver lower in the ear cup such that it fired more “upward” into the ear, the problems with the 4-5 kHz region could’ve been acoustically mitigated somewhat.

Otherwise, things like removing the dust cover or the felt on the driver only seem to make the headphone worse, so there aren’t really any mods I’d recommend someone do for this headphone.

If you’d like to try an EQ I generated for this headphone, I’ve shared it as well as suggested customizations below: But I make no guarantees that it is an improvement, because for the reasons stated above, I can’t have much assuredness in how the headphone will behave on the head of other listeners.

Preamp: -6.0 dB

Filter 1: ON PK Fc 72 Hz Gain 2.0 dB Q 1.400

Filter 2: ON PK Fc 150 Hz Gain -7.2 dB Q 0.200

Filter 3: ON PK Fc 650 Hz Gain 3.0 dB Q 0.900

Filter 4: ON PK Fc 925 Hz Gain -2.0 dB Q 2.400

Filter 5: ON PK Fc 1300 Hz Gain 1.4 dB Q 1.000

Filter 6: ON PK Fc 3200 Hz Gain -2.0 dB Q 2.000

Filter 7: ON PK Fc 4750 Hz Gain -9.5 dB Q 1.800

Filter 8: ON PK Fc 5900 Hz Gain 10.0 dB Q 3.200

Filter 9: ON HSC Fc 9900 Hz Gain -5.0 dB Q 2.000

Filter 10: OFF LSC Fc 105 Hz Gain 0.0 dB Q 0.700

Filter 11: OFF HSC Fc 2500 Hz Gain 0.0 dB Q 0.400

Adjust Filter 7 for cutting the 4-5 kHz peak

Adjust Filter 8 for filling in the massive dip

Adjust and engage Filter 10 for overall bass level

Adjust and engage Filter 11 for overall treble level

Grell OAE-1 vs. Sony MDR-MV1

I’ve chosen to compare the OAE-1 to the MDR-MV1 because I think MDR-MV1 does basically all of the things OAE-1 does, but better.

Before we even get to the sound, the MDR-MV1 is one of the most comfortable headphones I’ve ever put on my head. The headpad is adequately thick at best, but the weight is so light (~220g) that I think the subpar headband padding is easy to get away with. The earpads are ear-shaped, not circular, and loosely-wrapped in fairly soft microsuede. There’s a bit of my ear that touches the baffle, but the clamp is much more forgiving than OAE-1 such that overall, comfort is a night and day difference with MDR-MV1 taking a decisive lead.

In terms of frequency response tuning, they’re actually rather similar until the upper mids. I find both to be much too bassy for my taste and not especially impactful or dynamic due to the over-warmed presentation below 1 kHz. In the upper mids, the peak of MDR-MV1’s ear gain is much more forgiving such that I don’t get any of the “concrete-esque” harshness that OAE-1 has going for it. However, MDR-MV1 does have a lot of mid-treble, and it bothers me even more than OAE-1’s mid-treble cavern does.

I find MDR-MV1 similarly unimpressive as OAE-1 in the subjective department. It improves moderately in the realm of “detail,” where I hear it as sounding much more complete on smaller cues especially. But otherwise, I don’t think I’d recommend either of these based on the strength of their subjective performance.

Remember when I mentioned that OAE-1 might be a good EQ platform because in open headphones the consistency across heads may be better? The MDR-MV1 is a great example of an open headphone with comparatively minimal change across heads, such that if I were recommending an EQ platform to anyone under HD 800S pricing, MDR-MV1 would be the headphone I choose. Grell OAE-1 is, by comparison, particularly poor for this above 1 kHz as far as open headphones go.

I’d definitely recommend MDR-MV1 over OAE-1, because as a product it’s just more well-rounded and better suited for long-term use. However, MV-1 has its own issues that, were I writing a review solely for it, I’d probably not recommend it on its own merits without EQ.

Grell OAE-1 vs. Sennheiser HD 600

A huge reason I got fired up enough to write this massive piece is because of people saying “OAE-1 shouldn’t be judged against HD 600, as their design goals are different.”

To me this just sounds like “we should not compare OAE-1 to things that sound good.” I do not get whatever the point behind this is supposed to be, but I gotta be upfront: it makes no sense. If I’m spending $400 on a headphone, you better believe I’m going to compare it to the toughest competition I can reasonably find… especially when it was made by the same guy.

Sennheiser HD 600 Headphones

If OAE-1 is a brave attempt at something novel—and credit where credit is due, it is brave—then the way to figure out if the risk was worth taking, or worth adopting in earnest for other products going forward, is exactly to test it against things like HD 600 and see which one people prefer and why. Especially because HD 600 is tuned according to a diffuse sound field, so it makes for a convenient “Diffuse Field” opponent to OAE-1’s “frontal HRTF” oriented tuning.

Unfortunately, OAE-1 gets absolutely destroyed in this fight. And people are going to say I’m being hyperbolic, or dramatic, but I’m really not.

To even treat this as a serious competition would be disingenuous of me. OAE-1 doesn’t sound normal on a single thing I’ve listened to, whereas HD 600 is—on average, across listeners—in contention for the most normal sounding headphone of all time. I don’t get any notable subjective impression from OAE-1, whereas HD 600 is one of the more detailed and nuanced headphones in its price range.

I could go on about how the HD 600’s design is more normal and comfortable, how it is probably one of the only headphones out there with a positive reputation for build quality, and how it is literally the most legendary audiophile headphone of all time… but I’m sure you guys get the point.

Conclusion

You’ve probably guessed this by now, but I’m not going to be recommending OAE-1.

Just because I’m not going to be recommending it doesn’t mean it’s impossible that you’ll enjoy it, though. And just because I say soundstage doesn’t really exist the way most people think about it doesn’t mean there isn’t something special about how the OAE-1 presents space on your head.

It might seem like I’m unilaterally making claims about the headphone being objectively poor, or spaciousness not existing, but I do genuinely believe the above: I can’t know with any certainty what is happening for a given listener who isn’t myself, so feel free to take all of the above with as many grains of salt as you’d like.

People will buy Grell OAE-1, and despite me thinking they probably shouldn’t, there are still valid reasons to do so. Some want a novel sonic presentation, some want to own a piece of audiophile history, and some just want to support one of the greatest headphone designers of all time. Hell, I even considered buying OAE-1 despite knowing how terrible the sound was going to be, just to support Axel and own a piece of his history. I only didn’t because I got time at home with the unit featured in this review, and the comfort issues made it an absolute non-starter for me.

I’m just presenting my experience with a headphone that I—as an HD 800 lover—deeply wanted to succeed, while providing the context of my current read of the science and how it informs my perspective on this headphone’s goals. I’ve not seen anyone else bring forth this perspective in response to this design, so I felt it prudent to offer for those who haven’t been exposed to why people don’t make headphones like this anymore.

It’s because regular old Diffuse Field—as well as other targets—are both theoretically and preferentially superior, and they have been for roughly 40 years.

An incredibly open acoustic design is still a really cool idea that I’d love to see explored in more headphones after OAE-1, but I think the extreme frontal incidence of the driver of OAE-1 is almost entirely responsible for this headphone representing more of a failure to prove a concept than anything else.

The marketing story of the driver’s frontal orientation giving it a presentation akin to speakers was a rather good excuse for otherwise poor acoustics, and unfortunately I think many people will actually buy into it.

But it’s the job of reviewers to try and make sure that consumers and readers are equipped to have reasonable, well-informed doubt when claims like this are made. So hopefully this review means that next time a reader sees claims about soundstage, they’ll think a little bit harder about what that actually means. Thanks for reading.

If you have any questions or want to chat about this article, feel free to ping me in our Discord channel or start a discussion below on our forum, both places being where you can find me and a bunch of other headphone and IEM enthusiasts hanging out and talking about stuff like this. Thanks so much for reading. Until next time!