The DUNU Mirai: A Glimpse into the Future

The Mirai was designed to encapsulate the sound of the future. In this article, Precogvision dives deeper into the tuning process and more details about his first collaboration IEM.

The Past

Precogvision here. I’m a reviewer who’s been on the audio scene since my freshman year of college way back in 2020. When a global pandemic put the world on house arrest, I found solace in reviewing audio products. I earned a reputation for my critical reviews, and I continued building a platform alongside Headphone.com’s team over the last several years.

But I’m someone who believes in self-improvement and purpose. I had to wonder, what can I do to take my involvement with this hobby to the next level? I don’t have the technical expertise to build my own IEMs, and I don’t have the know-how to perform audio research. But I sure as hell can communicate what I like (and don’t like) hearing. The natural answer was a collaboration IEM that would bring my idea of good sound to other listeners. As I churned around this idea in late 2021, the first roadblock I stumbled upon was which manufacturers I could collaborate with. Then possibly a more important question: Which manufacturer would even be up to the task?

At the time, Thomas Tsai was DUNU’s Head of Market Relations, and we’d had numerous in-depth conversations about their IEMs in the past. He knew what made IEMs tick, he knew the nuances of the manufacturing process and, best of all, he was extremely open to ideas and shaking up the status quo with collaborations.

I should expand on this so-called status quo. Collaborations are often difficult to facilitate due to language barriers, locational proximity, and logistics. This is to the point of which a collaboration can easily blur into “just hit this frequency response target” or “let’s just put your name on this IEM”. By contrast, from the start, we (DUNU, Headphones.com, and myself) established that we didn’t want the Mirai to be like other collaborations. We would work as a team on each step of the process to build the Mirai from the ground-up.

Early Stages

Every product needs a catchy name that embodies the spirit behind it; as someone who writes for a living, I should know from experience the power of words. My own moniker, Precogvision, is a play on the words ‘precognition’ (meaning foreknowledge of a future event, especially of paranormal nature) and ‘vision’. It was natural that the name of the collaboration IEM should stay consistent with this theme: anticipation, prediction, and maybe a little magic.

I proposed over a dozen naming ideas which Thomas and I deliberated over. We meticulously considered the wording and implications of each name before agreeing on a name:

Mirai (noun)

- The future

- The world to come

The Build

We churned around a lot of ideas for the driver configuration of the Mirai too. At the time, the SA6 was my favorite IEM from DUNU, and my initial thought was that it would make a great starting point. But we also wanted to build something from the ground-up, so that idea was scrapped pretty early on. Thomas also brought up the idea of a planar hybrid setup at one point (which I believe became the DUNU Talos). Additionally, though, I’ve never been quite sold on the fancy driver configurations hitting the market, as more complexity means more things to go wrong. Hence we decided to go with a traditional hybrid (DD/BA) setup.

This was the result, Mirai.

I've been a longstanding fan of DUNU's DUW02 cable for its ergonomics and pliability, so it was brought back for the Mirai in a special edition white colorway. Of course, it also sports DUNU's legendary termination swap system.

While I had a vision and strong opinions about how I wanted “my own” IEM to sound, there was so much else that I simply hadn’t considered before diving into the project. Market competition, minimum order quantities, materials, and logistics were just a few headwinds that I was unprepared to navigate. There was a lot of additional thought that went into designing the Mirai’s packaging and physical aesthetic.

Luckily, I wasn’t alone. While I provided a general outline and ultimately gave the green light, the majority of the credit has to go to the talented engineers and designers at both DUNU and Headphones.com that brought these aspects of the Mirai to life.

The Tuning Process

I did spearhead the direction of the tuning, though, so let me fill in the details of that process.

The first round of feedback occurred when I was at CanJam Singapore 2022; DUNU sent a prototype over to one of their retailers in the country, SAM Audio. I was eager to have my friends in Singapore take a listen because they were veterans who, like me, had heard hundreds of IEMs. They could give me informed and honest feedback. And they did: they all agreed that this first round was a pretty big disappointment. I couldn’t say they were wrong, and I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have concerns about the whole collaboration at this point. In any event, it was definitely time to hit the drawing board again, so we could produce something that didn’t sound like a $100 budget IEM.

The second prototype illustrated the complications of not only the language barrier but also a clash of ideology when it came to tuning style. International audiences, especially those in China, tend to prefer a leaner and brighter sound signature.

This new prototype sounded good with sharp transients, exceptional treble extension, and unique imaging. Except this presentation was far removed from what I wanted it to be. It had all the other issues associated with this type of tuning, such as a lack of bass response and sounding too strident. Recognizing this complication, I assembled a document illustrating the qualities that I desired in sound and sent them to DUNU’s chief engineer, Andy Zhao, so that he could cross-reference them with his own ideas.

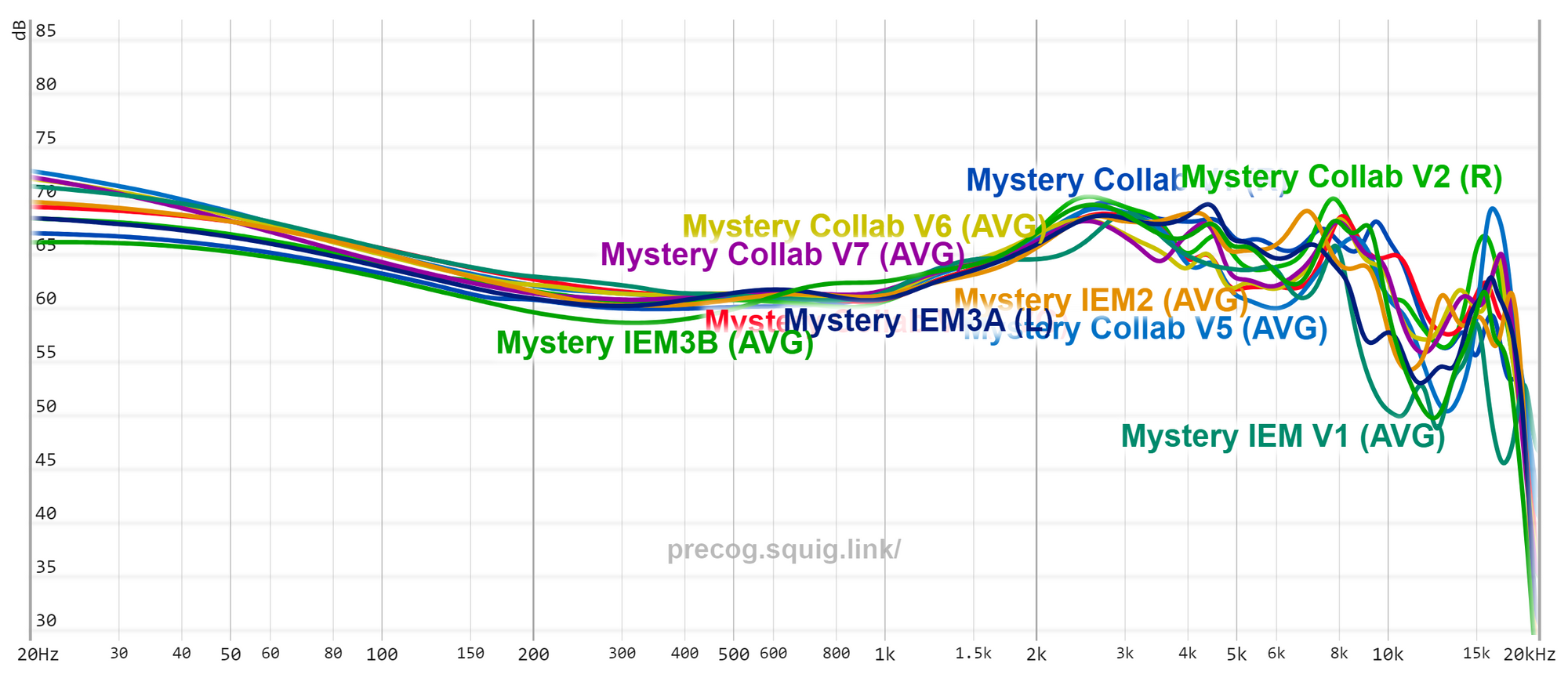

Several of the prototypes that I provided feedback on.

The next several iterations of the collaboration IEM steadily improved, but showgoers that listened to those prototypes at CanJam Socal 2022 and NYC 2022 mostly had mixed feedback. I certainly wasn’t satisfied, and I consistently sent us back to the drawing board. A complication that became evident was balancing comfort with sound quality, as the two are often inversely correlated. Think of some of the best sounding IEMs like the Sony IER-Z1R, the Symphonium Helios, and the Subtonic Storm - they all sport relatively large shells.

Currently, Mirai utilizes a metal nozzle that is hand-fitted. We tried implementing a 3D printed nozzle instead which was stouter and which would have dramatically streamlined production. But I had to shoot this down because the performance sound-wise wasn't comparable.

This complication required fastidious revisions of the Miria’s nozzle integration. But finally, the hard work and unwillingness to compromise paid off with the last couple rounds of prototyping. We had a version that I thought sounded great, and a final, small adjustment to the tuning on DUNU’s end brought something to the table that I wasn’t sure was even initially possible.

Why does it sound like that?

Let’s take a step back to my early days of the hobby. During this time, I remember neutral-tuned IEMs, especially those influenced by the Harman target, as being all the rage. But when I purchased my first IEM tuned to this target, I found myself disappointed by the almost clinical presentation. This became a consistent pattern as I got my ears on more IEMs, and it only mounted as the market became more populated with these types of tunings.

Basically, there is a wide range of listener preferences, and I’ve always found myself attracted to tunings that break convention tastefully. I don’t think I’m alone either: the majority of flagship IEMs are not IEMs that follow conventional tuning strategy. That in mind, let’s talk about my thought process when I was tuning Mirai and who it might appeal to.

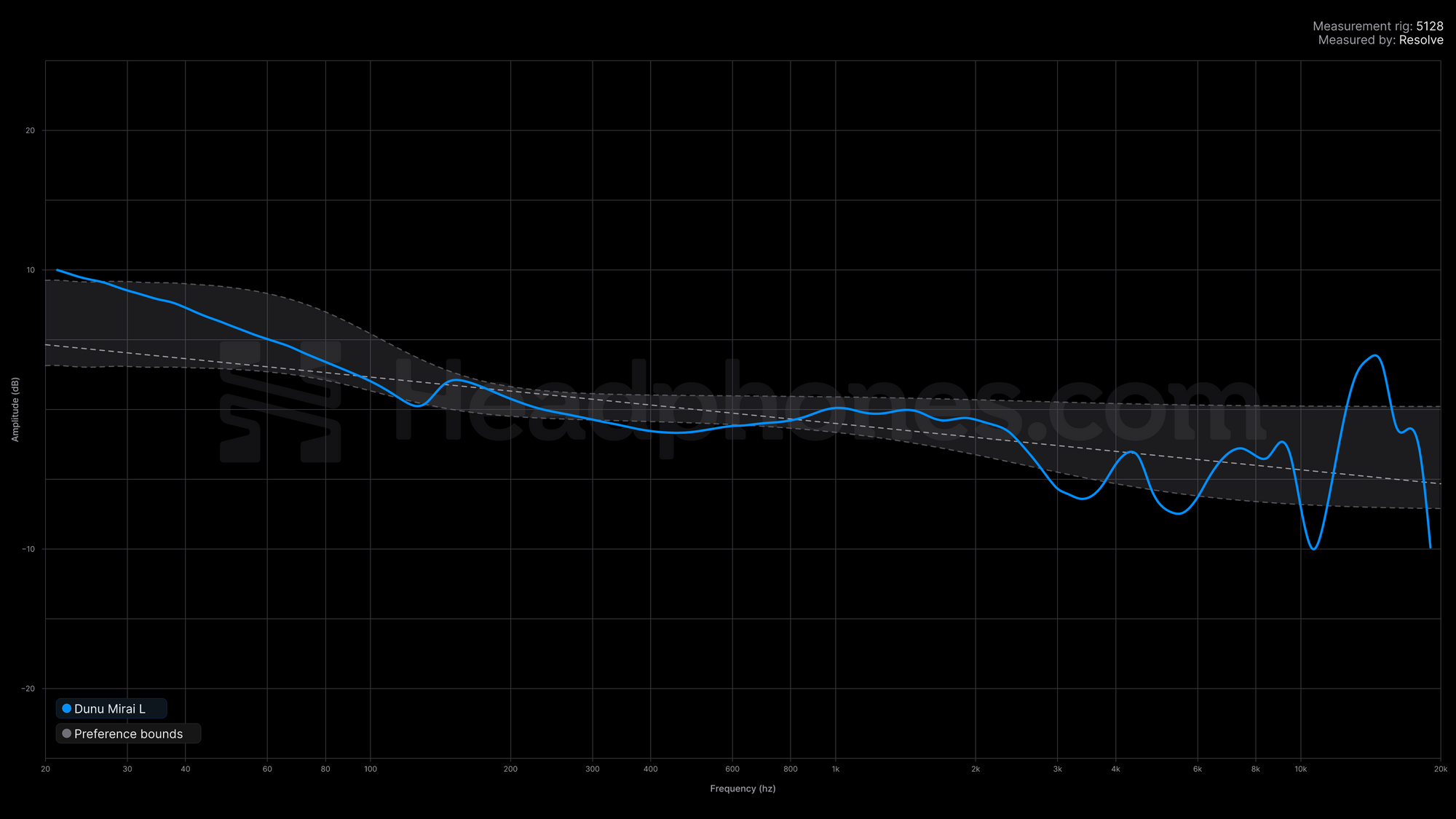

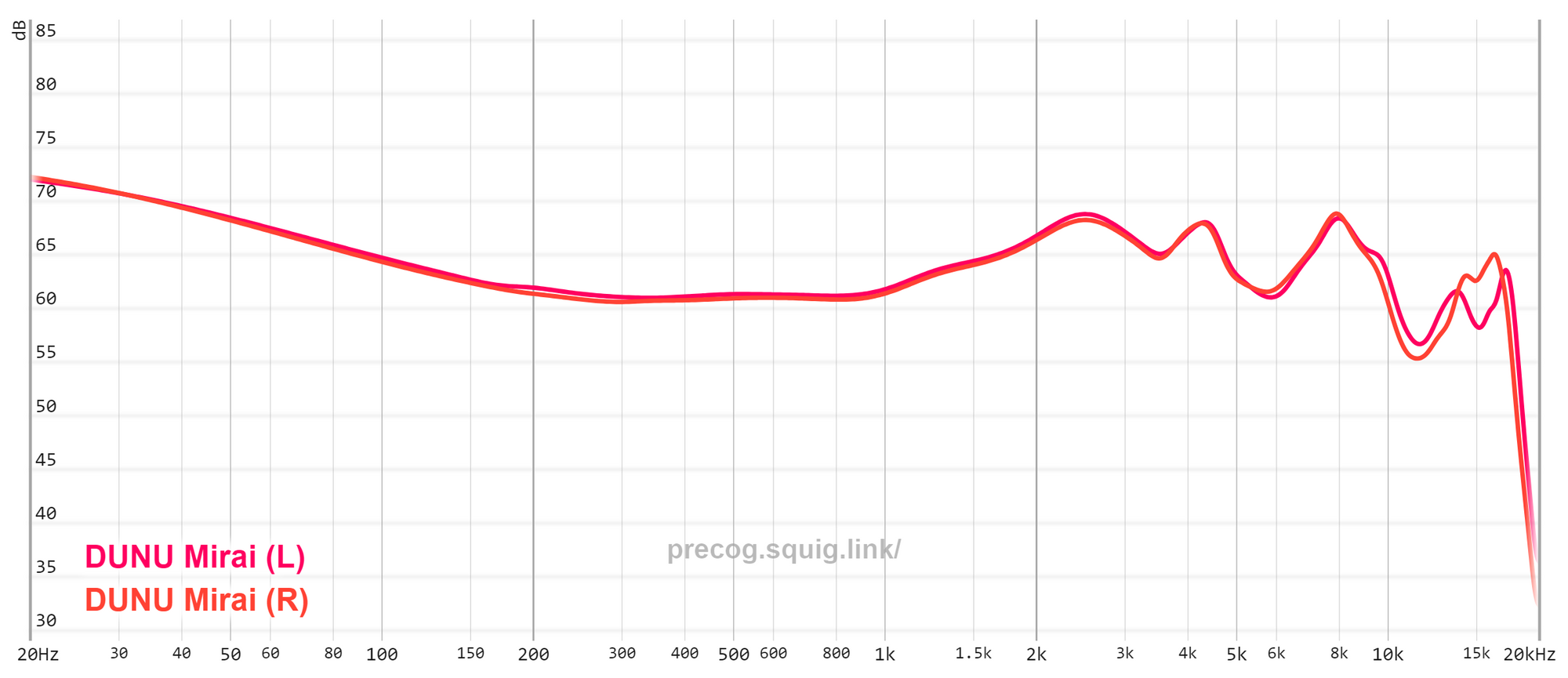

This measurement was taken on the newer B&K 5128 system. The preferences bounds indicate the range for the sound profile that most listeners would prefer based on our research.

Readers looking for more information can check out this explanation by Resolve.

This measurement was taken on my personal clone IEC-711 coupler. It can be used as a comparison to hundreds of other IEMs that I have measured and uploaded to my SquigLink.

A criticism that I had with earlier prototypes of the Mirai was the bass response. The early prototypes lacked appropriate quantity in the sub-bass and they tended to be shelved too early (with minimal mid-bass). Thus, we steadily ramped up the bass. The current iteration has ~10db of sub-bass over 1kHz with a smooth taper into the mid-bass that ends at ~250Hz. It sounds neither disconnected (like a sharp recession to bass at 200Hz will create) nor muddy from excess mid-bass. Bass is present when called upon, controlled and highly coherent for a hybrid IEM.

But the magic behind the Mirai’s sound mostly lies in its transition from the upper-midrange to the treble response. Conventional tuning strategy says that these regions should mostly fall in line with each other or follow the declining trajectory of a parabola. Comparatively, the Mirai’s tuning not only reduces the presence region from 2.5-5kHz but also sports a series of small peaks in the treble (most noticeably at ~10kHz and ~15kHz).

So why did we choose to disregard conventional tuning strategy? There’s several reasons:

- A sense of shouty-ness often results from an overly forward 3-5kHz region. Too much energy in the 6kHz region can also result in sibilance. By giving the Mirai a more “polite” response in these regions, we are able to circumvent these common pitfalls.

- A slight bump of energy at 4kHz brings back some of the ‘bite’ that might be missing if these regions were entirely reduced.

- As frequencies rise, especially in the upper-treble, our ears become less adept at distinguishing between individual peaks. If peaks are kept in quick succession, or they have similar amplitude between them, listeners will hear something closer to a linear brightness.

These tuning decisions were influenced by my experience with IEMs that not only have superior treble extension (think IEMs like the Symphonium Helios and Elysian Annihilator), but that also have unusual peaks and valleys (think the 64 Audio IEMs). The common denominator is that all these IEMs are standouts for subjective technical qualities like resolution and imaging.

In essence, treble response past 10kHz has a crucial effect on imaging performance; appropriate quantity creates the sensation of instruments “floating” around the stage. A sensation of openness to the soundstage can be further enhanced through the use of recessions in frequency response, hence the Mirai’s more polite 3-5kHz region. Finally, the more polite 3-5kHz region relative to the more energetic upper-treble increases dynamic contrast and engagement factor.

The end result? To my ears, the Mirai particularly shines with female vocals, as it’s non-fatiguing while maintaining a strong sense of ‘edge’ (or detail) to midrange transients. Tracks with high-frequency content sound more immersive; musical content positioned at the center of the soundstage pops out and seems to have more room to breathe. The Mirai aims to spice things up for seasoned listeners as much as it aims to impress those dipping their toes into the world of high-fidelity.

What about conflict of interest?

There's no ignoring the elephant in the room: Mirai is a conflict of interest. There’s nothing I can do that will change this (short of quitting as a reviewer). But I can do my best to massage some doubts.

Financial motivation is the most obvious culprit. And while I usually shy away from talking about personal finances, I have to point out that I don’t review for a living. My content work makes up less than 10% of my total income. Basically, I don’t have a strong incentive to push sales of my IEM. I'm very fortunate to be in a position where what I make from my full-time job is enough to sustain myself and dwarfs what I make from reviewing.

More importantly, I’ve also built up a strong reputation for honesty. I see this as a long-term feedback loop, where people keep coming back to my reviews because what they experience is consistent with what I write, or I offer a useful perspective. If I suddenly switched up by panning everything as being worse than Mirai, I would be breaking this trust. It’s difficult to build trust, it’s easy to break it.

On a more sentimental level, the goal behind Mirai wasn’t entirely about turning it into a collaboration to sell to the market. I really just wanted an IEM that I could call my own, with my idea of good sound. But you need resources to build your own IEM, and there needs to be a reciprocal relationship to springboard development, hence why it became a collaboration.

For those curious, Resolve and I dive deeper into the topic of conflict of interest in this video.

Mirai: The Future

To circle back to the meaning of this collaboration’s name: what does the Mirai mean not just for my own brand, but also future collaborations? As I alluded to earlier, the market has seen an explosion of collaboration IEMs. And while the idea was initially unique, the format has been quickly commoditized to conform with the IEM market’s cyclical nature.

By contrast, I’d prefer the Mirai not to be thought of as ‘just another collaboration IEM’. It’s a culmination of passion, ideas, and labor from multiple parties. I want it to stand the test of time, so I’m not interested in quickly releasing another collaboration IEM. And if I do release another IEM with my name on it, you can rest assured that it would have to meet the high bar that Mirai has set. But for now, in the present, I’m looking forward to more listeners finally getting their ears on my first collaboration set.